Brother Joseph Alak, serving in South Sudan provides us with background information on the new country. It is clear that the new school is desperately needed…

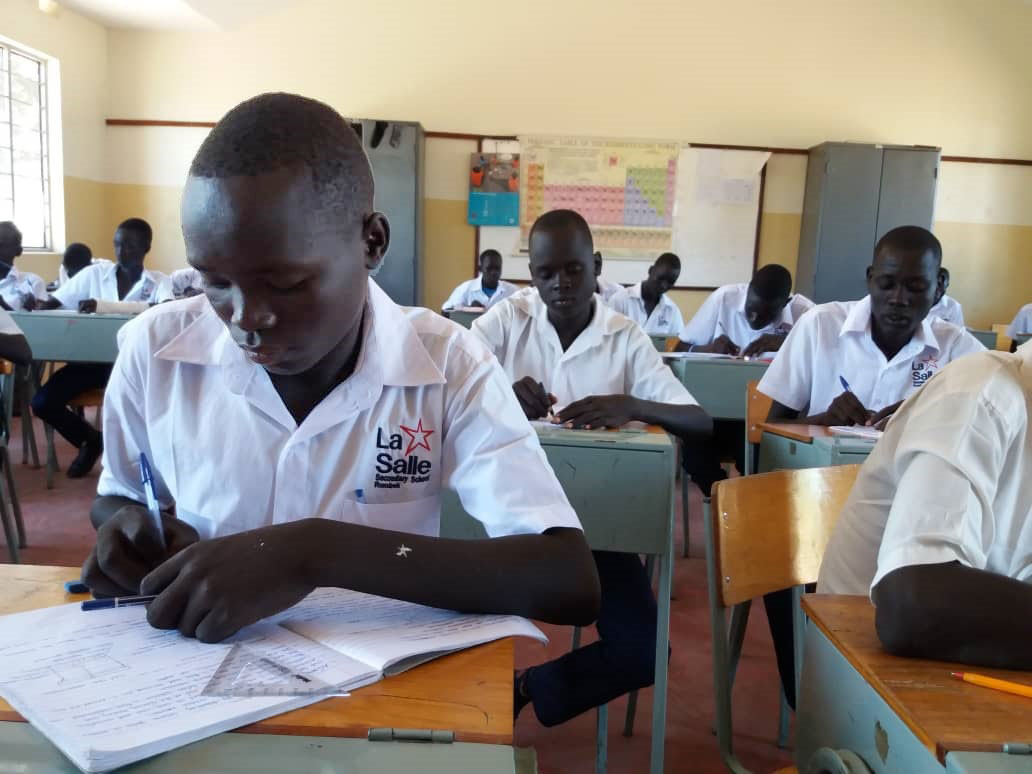

La Salle School, Rumbek opened its doors in 16th March 2018 with 26 form ones. Since then, we have added 45 form one students for this year 2019, and added 2 learners to form twos. The current we have 73 students. The school is under construction as we speak, the phase will include 2 blocks classrooms, Brothers’ community, Staff block and a dormitory for boys.

Classes began for our students from the new secondary school in Rumbek, South Sudan! They are now hosted in the existing facilities of the Loreto Sisters School until the new South Sudanese school year in February 2019.

The challenges that are facing us in the moment are lack of infrastructure as the school is still under construction and the classrooms are not ready. I hope that after few months, the classes will be ready and the boys will move in.

Until this time, the two Brothers (Julius and Eustace) are residing in the cathedral quest house called Pan door, where we are paying $ 40 per day for their accommodation and feeding, and I am residing in Loreto premises.

I see the impact of the school from the candidate that applied for form this year, we needed only 45, but the applicants were more than 180 students. Just one year and the learners around Rumbek want to be in our school. I don’t know what will happen in the future as the rest of South Sudanese learn about our school in Rumbek.

Why are we fighting each other?

Good question. South Sudan is a good country, but it has been destroyed by its own residence through corruption, tribalism, nepotism and other things. Tribalism is the cause of suffering of the people of South Sudan; also, a lot is blamed on the illiteracy of it citizens which cause poverty, sickness and death. If only we could focus on these things and try to solve them, our land will be at peace with itself. Immediately after independence, there was togetherness, love and Peace and we were respected as a country by the world.

Political Setting

South Sudan is in a state of crisis: its people suffered under state collapse, political repression, armed conflict, economic breakdown, ethnicity violence, famine and displacement among others.

South Sudanese agree on the need for fundamental change. But a solution is hard to find: since independence in 2011, repeated political, economic and military crises and dishonored peace agreements have resulted in exhaustion and bad faith on all sides.

There is little common ground, coherent, or shared understanding of the problems and of possible ways forward.

- The current conflict is a result of South Sudanese ‘tribal mindset.’ International observers and national actors in South Sudan blame popular tribalism and inter-ethnic violence on the heterogeneity of the country’s ‘64 tribes’: a nation of distinct nationalities, each ‘in their own separate enclaves’, and entrenched in tribal patterns of political logic because of a general lack of education or literacy.

The country’s cultural and social diversity, its complex histories of migration, and the interlinkages of languages, ethnic sections and clans are often condensed by South Sudanese political agents and harried humanitarians into discrete supra-ethnicities like ‘the Dinka’ or ‘Nuer’, with bounded territories, and long separate tribal histories. This is a fundamental misreading of both the political instrumentalization of ethnic identification in South Sudan today; and the long history of the nation’s population.

Groups often referred to as ‘historical enemies’ – such as ‘the Dinka and the Nuer’ – have been linked for centuries through trade, intermarriage, migration, linguistic commonalities and creolization. The people of South Sudan are differentiated primarily through ancestry, family clans, linguistic specificities, migration routes, and political histories.

Many of the myths around ethnic identity in South Sudan – specifically, that South Sudanese people view themselves primarily through tribal lenses, rooted in a bounded ethnic territory, and governed by chiefs and elders are the same assumptions that underpinned the late colonial strategy of the British administrators of the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium from the around 1900 to 1956.

This political tribalism has been mobilized by colonial and post-colonial governments, and by the independent government of South Sudan today, as a useful tool in seeking constituencies of support; and has been entrenched locally by successive governments’ impositions of administrative boundaries and structures set on, or set up to exploit, ethnic solidarities and competition for central resources, land, and power.

- Humanitarian dependency: South Sudan and its people are overly dependent on foreign aid; South Sudan is commonly understood as being a severely undeveloped subsistence society, divided into pastoralists and agriculturalists, who continue to fight age-old conflicts over land and grazing rights.

Many humanitarians emphasize how, after successive civil wars and displacements, the population has become dependent on aid; international observers frequently decry how humanitarian and donor funds appear to be underpinning the economy.

The country’s rivers, plains, flood patterns, forests, and cross-border ecologies and migration routes create many regional systems, rather than national, economic ones.

7 Million South Sudanese are in desperate need of Humanitarian Aid.

Food Security

- 6 million South Sudanese facing Crisis Levels of Hunger (as much as 64% of the population)

- Rumbek Center has been in Crisis or Emergency levels of Food Insecurity for over 3 years.

- 87.7% of households report being moderately to severely food insecure.

- 80.8% reported low food consumption.

- 89% reported moderate to severe hunger.

- Half of the population of South Sudan does not know where their next meal comes from.

- Loreto Primary (w/ALP) Students only get 0.35 meals per day outside of school (one meal every 3 days during the rainy season, as little as 1 meal every 5 days during the dry season.

- Over 66% of breastfeeding women suffer from acute nutritional deficiencies.

- Cost per meal: $ 0, 57. Costs could be as low as 0, 35 dollars per meal in the coming year.

- Cost per Metric Tones: 1,135 dollars

Agriculture

- Cereal Production deficit is projected to increase to 26% (reduced yields)

- Nearly 90% of the population relies on subsistence farming for survival.

- 94% of South Sudan is arable – only 4% is actively farmed – most farmers are small holder/subsistence farmers.

- Almost no mechanized irrigation available, no large-scale farming during 6 month dry season.

Economy

- Official Salary for trained teachers at Primary or Secondary Levels is 900 SSP (less than 4 dollars); most teachers are still paid the standard salary of 300 SSP (les than 1,25 dollars).

- Teachers are considered to be of lower value than Drivers according to South Sudan’s order of civil servants where teachers are a class 9 and drivers are class 6.

- 3.5 KG of Sorghum costs 474 SSP or ~2 dollars.

- Employment remains under 12% in Rumbek, employment rates may be as low as 3%.

- South Sudan relies on imports – 90% of staple commodities are imported to South Sudan.

- NPSIA says that there are “no stabilizing economic factors” in South Sudan currently.

- Currency is wildly speculated upon.

- 81% of teachers reported being paid 40% or less of the months worked in 2017.

Health

- 88% of students lack access to primary health care service; 96% lack basic first aid.

- Only 1900 medical facilities in South Sudan; 20% have been closed and nearly 50% were functioning at extremely limited capacities.

- Only 21% (400 facilities) were considered to be operating at “functional Levels”, only 500 facilities (26%) were functioning at more than 10% capacity.

- 34% of women face anemia.

- Under 5 mortality rate of 9.1%.

- Over 2 million cases of Malaria reported in 2017 (16% of the population, 31.1% of clinical consultations).

- Lack of facilities, qualified staff, equipment and medicines cripple the existing system.

- Loreto PHCU provides an average of over 1800 Clinical consultations each month.

A blank slate: South Sudan started from nothing when it became independent in 2011.

It is close to five years since civil war began in South Sudan with negotiations failing to broker a peace deal between the warring groups. The unending conflict that started in December 2013 has resulted in destitution with thousands murdered and millions displaced.

Structurally, the primary reason why the conflict in South Sudan will not be ending anytime soon regards the distribution of wealth and the proceeds generated from the wealth. Internally and externally, conflicting interests among various groups have stalled the peace process and in any case, these groups continue to fuel the civil strife.

Internally, the desire to amass wealth is driving more entities into the war. Many people army formed a rebel movement with the intention of fighting against the current administration which they consider to have failed in regards to restoring peace in the country.

Each of the existing militia groups seeks to impose some form of territorial control over the regions which are considered to be highly endowed with natural resources. The corrupt nature of the government led administration prompted the onset of the crisis with his family members and cronies looting the country’s national wealth at the expense of the ordinary South Sudanese citizens.

Transparency International ranks South Sudan at position 179 out of 180 countries as per the 2017 Corruption Perception Index report. This implies that South Sudan is an excessively corrupt state.

The question of who controls what in view of the natural resources is fundamental in understanding the genesis and nature of the conflict. From the exploration of oil, to gold mining activities as well as poaching and trafficking of wildlife, few individuals have strategically positioned themselves to benefit from the country’s natural resources.

Externally, geopolitical and geo-economics factors continue to exacerbate the conflict in South Sudan. Both regional and foreign states have a hand in the unending crisis. The scramble for the natural resources in South Sudan and the benefits derived from the war occasion a number of states to hatch strategies intended to prolong the war.

Regionally, various states are responsible for the civil strife in South Sudan. For instance, Sudan has a hand in the chaos rocking the world’s youngest state. Before gaining independence, the south battled with the north for a record 22 years between 1983 and 2005 in what has come to be referred to as the Second Sudan Civil War.

Khartoum offers support, financially and militarily, to some of the rebel groups in South Sudan in order to prolong the conflict and in due course profit from the oil in Abyei.

Uganda’s interests in South Sudan play a major role in the conflict. Uganda is South Sudan’s largest trading partner with various Ugandan entities engaged in the trading of oil, agricultural produce like maize among other commodities. As reported in February last year, Uganda was set to import gold from South Sudan.

Is there any hope for peace in South Sudan?

The deal, signed by President Salva Kiir and former Vice President Riek Machar, was reached in the Sudanese capital, Khartoum, in the presence of Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir and Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni.

The latest agreement boosts hopes that peace may soon be reached to end the country’s four-and-a-half year civil war, which has killed tens of thousands, pushed millions to the brink of famine, and created Africa’s largest refugee crisis since the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

We are hoping that the new Peace Agreement will change the current political situation in the country, and that it will unite and reconcile the people of South Sudan. “Our leaders need to take this agreement seriously and should implement it in letter and spirit. We don’t need this deal to collapse again.”

A cease-fire that was agreed upon last year a half has largely held across the nation, no gun shorts. South Sudan’s neighbours–Sudan, Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia–are pushing to find a lasting solution to the hostilities in Juba, restore security, reduce the refugee burden, and boost trade and investment.

The Vatican visit: The meeting with the Pope was being seen as offering yet another opportunity to cement the Revitalized Peace Agreement.

Pressure is also coming from the United Nations to have President Kiir and signatories to the September 2018 peace agreement keep to their commitment and ensure a lasting peace, even as the Troika –the UK, the US, and Norway–who financed it remain sceptical.

Education

Education has been a primary issue in South Sudan as the nation endemically lacks high capacity staff to meet the demands of its own populations. The food security, economic, and conflict crises facing South Sudan have all detrimentally impacted South Sudan’s educational system. At the national level, South Sudan has approximately 1.8 million school aged children out of school, 8% of schools are non-functional due to damage, destruction, being occupied, or closed; as much as 26% of functional schools have been affected by attacks. According to UNICEF, South Sudan has the highest proportion of school age children out-of-school – 72%.

As noted by UNICEF, school operation has been highly impacted by conflict, resource constraints, and poor infrastructure. Sadly, a school only required to have only 1 teacher and for classes to occur, irrespective of the number of students, to be considered “functional”.

This means that schools can be considered functional without investment into classrooms, water resources, or school materials – all of which are important factors in education. Key informants at “non-functional” schools prioritized the rehabilitation/construction of school infrastructure, school feeding, and salaries for teachers as prerequisites for resuming functionality. School feedings have become a primary incentive for students amid the worsening food security crisis.

In 2016, there were only 14 secondary schools in the greater Lakes state with only 7 schools in our home county of Rumbek Centre. Lakes state has the lowest level of investment into secondary schools in South Sudan.

Educational infrastructure has suffered due to conflict and poor maintenance practices. The pupil to classroom ratio stands at 105.2 at the primary level and 44.0 at the secondary school level. In Western Lakes State, classroom sizes are higher with 130 primary school students and 68 secondary school students per permanent or semi-permanent classroom.